Stress – for survival

The adrenals

This pair of glands sit on top of the kidneys (‘renals’) and are made up of two main parts.

At the core is the adrenal medulla. This produces the hormones adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) as the body’s ‘fight or flight’ response to stresses. The medulla is an intrinsic part of the wider sympathetic nervous system, our instant reaction to alarming situations, especially where we need urgent extreme physical activity. So it

- increases heart rate and contractions

- moves blood to the muscles and brain (other blood vessels constrict so blood pressure also increases)

- relaxes airway muscles to improve breathing.

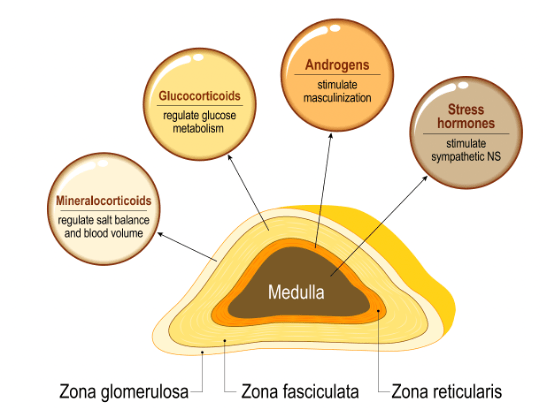

The first tissues affected by the medulla’s hormones are the surrounding adrenal cortex. This is divided into three zones, each responsible for producing specific steroid hormones.

- Cortisol: the first responder to adrenal medulla activity, and helping to manage the consequences. It helps control metabolism, manages inflammation, regulates blood pressure, increases blood sugar, and affects bone formation. It controls the sleep/wake cycle. It also feels good!

- Aldosterone: plays a central role in regulating blood pressure, acidity, sodium and potassium. It signals the kidneys to absorb more sodium and release potassium.

- DHEA and the androgens: precursor hormones for oestrogens and testosterone.

The adrenal cortex becomes particularly important in managing stress long term. It also shares most of its steroid producing functions with the gonads (ovaries or testes) having originated from the same tissue in the embryo. We will look at this link further down in this article.

The adrenals and stress

Modern clinical concepts of fatigue were linked to adrenal function after a brief 1936 article by the scientist Hans Selye, in which he introduced the concept of ‘stress’.

For Selye steroid hormones lay at the heart of the body’s capacity to adapt to the stress of life. In 1950 he elaborated, “the development and metabolism of the entire body, as well as its resistance and adaptability to exposure and disease, are influenced by the steroid hormones of the gonads, the adrenal cortex and the placenta.”

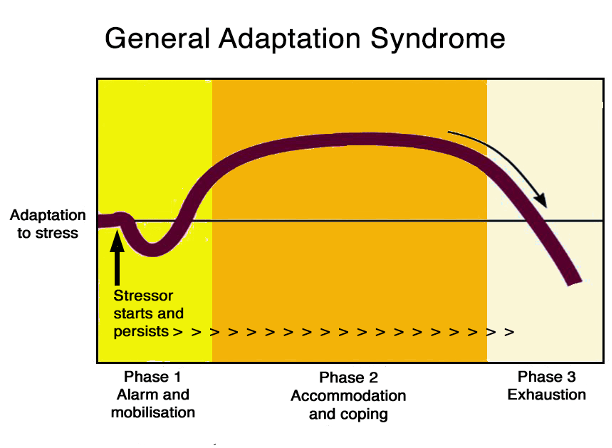

Selye’s article set out what appeared to be a three-phase pattern of responses to stressors: the ‘general adaptation syndrome’: this is made up of

- an initial alarm phase

- a stage of accommodation, resistance or adaptation, leading eventually to

- a stage of exhaustion.

Many since have linked this stress response to the capacity of the adrenal glands. The term ‘adrenal fatigue’ was coined in 1998 by naturopath James Wilson, as a ‘group of related signs and symptoms that results when the adrenal glands function below the necessary level’, this usually associated with intense stress and may follow chronic infections.

However blood tests do not usually pick up any reduction in adrenal hormones after stress and the concept is often dismissed in medical circles. More productive perhaps is to link the performance of the adrenals to their wider control system, the HPA axis.

HPA axis

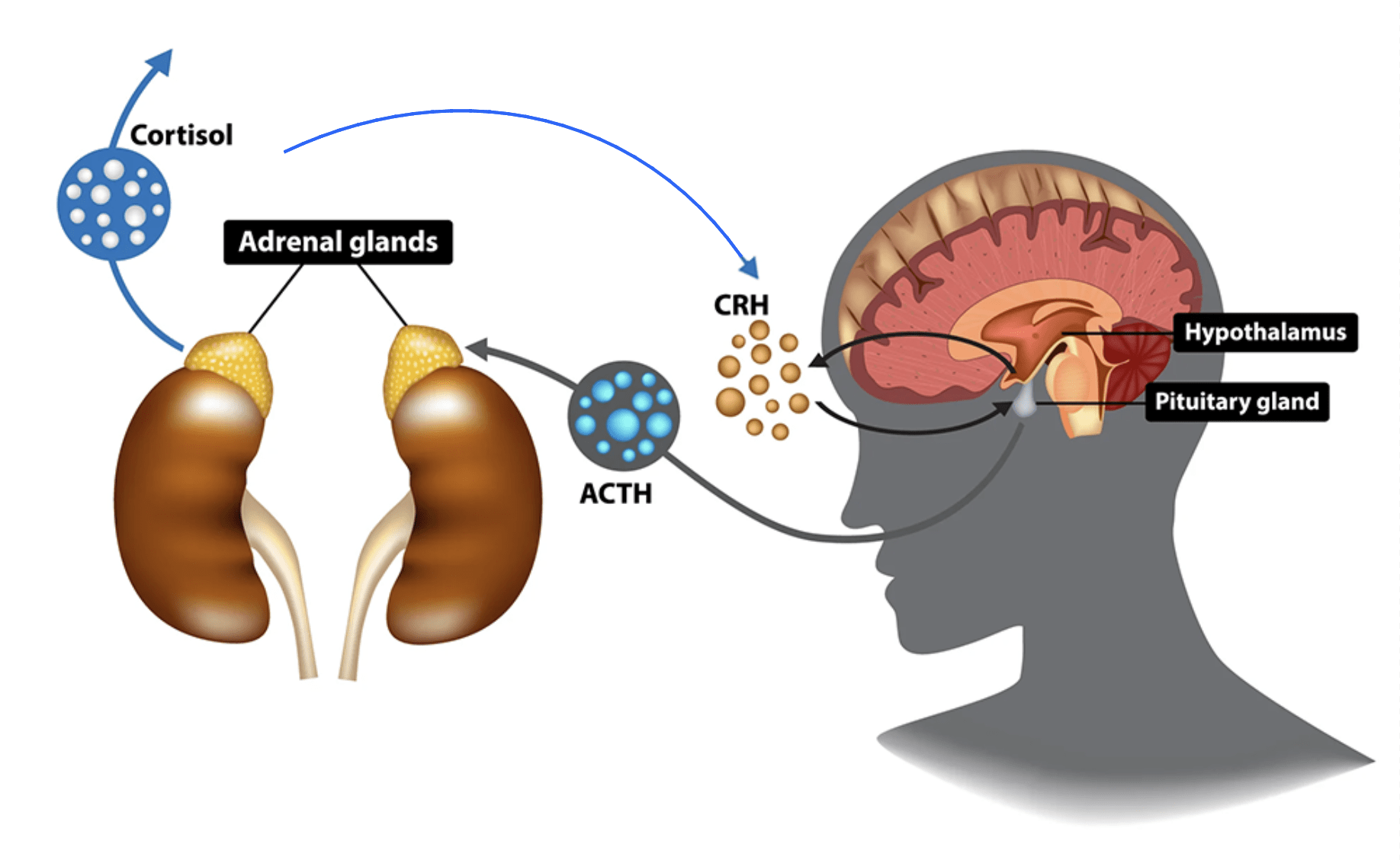

The primary hormonal stress response is a circuit that includes the adrenals, the pituitary gland and the hypothalamus, each producing hormones that regulate each other. A well-functioning ‘hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis’ is an indicator of resilience and coping capacity, and a more useful concept than focusing just on the adrenals.

A common feature of chronic fatigue appears to be reduced activity in the brain centres, including less adrenal-supporting messenger hormones: corticotropin-releasing hormone [CRH] and adrenocorticotrophic hormone [ACTH]) – see diagram. This then depresses adrenal cortex responses.

The consequences of underperformance of the HPA axis include disrupted sleep patterns (leading to a vicious cycle of increasing fatigue that exacerbates all CFS symptoms). All this is also shared with the causes of clinical depression. This is a common feature of CFS and has led to an unfortunate conclusion among many doctors that chronic fatigue is a form of depression.

Menopause – another adrenal dimension?

There is an important consequence of the common origin and functions of the adrenal cortex and ovaries in the experience that many have during and after the menopause. Both sets of glands produce the same hormones in the same way, though with relatively more oestrogens and progesterone and less aldosterone in the ovaries. Nevertheless there is a sharing of roles. This is lost at menopause when the ovaries close down. Many problems of menopause can be helped with extra attention to the adrenals and HPA axis.

Unique herbal approaches to adrenals and the HPA axis

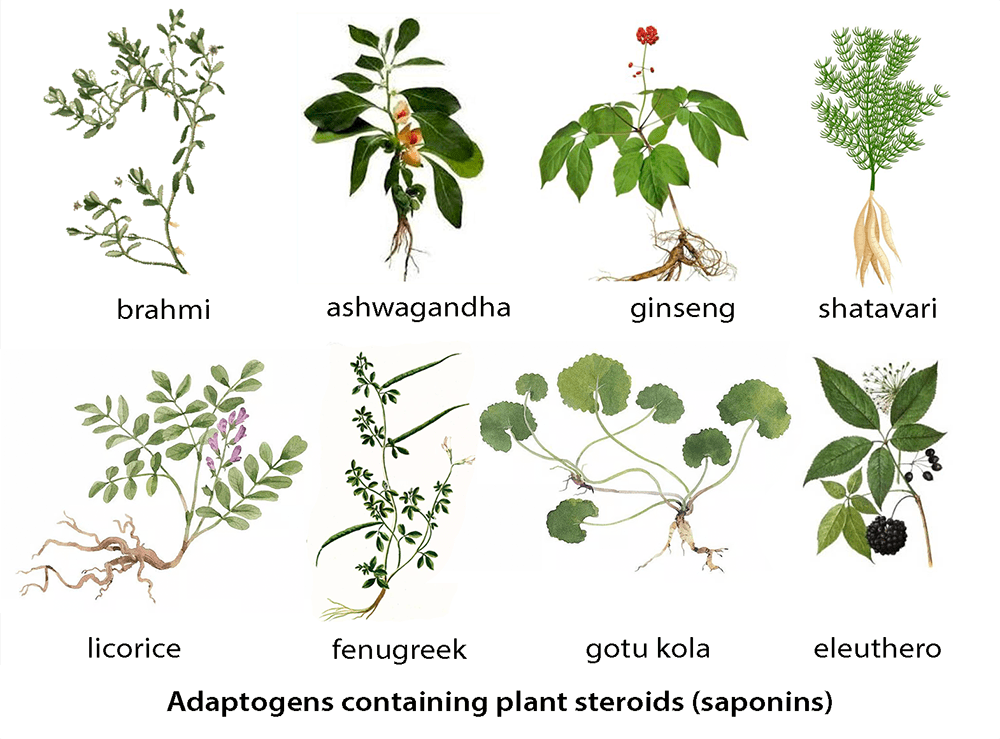

For many centuries, in many parts of the world, people have chosen ‘tonic’ remedies to help in the most demanding situations, including in convalescing from severe injury and illness, managing battle fatigue and maintaining health in old age. Many of these, particularly used in Asia, have since been found to contain saponins, in effect plant steroids. They do not replace human steroids but appear in some way to interact with steroid functions: candidate mechanisms include ‘nuclear receptors’ that normally mediate steroid activity in cells (see the technical review papers below if you want to learn more). Classic examples of widely-used tonic plants with high levels of sapnins are ginseng, eleutherococcus, licorice, gotu kola, ashwagandha, shatavari and bacopa. These and other remedies that apparently help with the body’s stress responses have been called adaptogens. We will look at the potential for using these in the final articles of this Fatigue Issue.

Interestingly high-saponin herbs often feature among those chosen by women for problems of fertility, menstrual cycles, menopause and childbirth. The common functions of ovaries and adrenal cortex become relevant again!

Thyroid

This gland produces hormones (T4 = thyroxine or T3 = triiodothyronine) that regulate metabolism (processes converting food into energy) and help to regulate body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure. It is more active during growth, pregnancy or when the body is cold.

Fatigue can be a symptom of two different thyroid problems.

In underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) a common symptom is tiredness. This may be associated with weight gain, depression, and sensitivity to cold. Most often this used to be caused by deficiency of iodine in the diet (eg inadequate seafood) but where iodine supplementation is widespread is now commonly the result of an immune attack – Hashimoto’s disease – and is most often treated with thyroid hormone replacement therapy, usually with levothyroxine (T4). The thyroid also produces calcitonin, a hormone that keeps calcium in the bone. In underactive thyroid this can also dip, leading to raised blood calcium levels that cause tiredness with muscle weakness.

In an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) tiredness and weakness may be accompanied by nervousness, anxiety, irritability, mood swings, and difficulty sleeping. This also most often has an autoimmune cause – Graves’ disease – which is conventionally treated with antithyroid drugs, such as carbimazole.

Plants have a range of effects on the thyroid, although probably only when consumed in large quantities. Some like brassicas and soy depress the thyroid if they make up a large part of the diet, and other plant constituents may have similar properties. Other plant constituents may have supportive action though most diets won’t have significant impact. Seaweed and other high-iodine supplements are only helpful for iodine-deficient thyroids (iodised salt or seasalt usually provides what is needed in this case though cutting back on salt may open upmthis problem again). Some plants have been postukated as thyroid remedies but the evidence for these is meagre (eg. some evidence for ashwagandha and turmeric in animal studies).

One must be careful about thyroid supplements. Many contain unregulated thyroid hormone and where this is derived from animals there is a concern about these having too high a percentage of more powerful T3 than human thyroids.

A better approach is to see the thyroid as wholly integrated into the wider orchestra of hormone producers and nervous control systems in the body. If not working well it may be better managed by looking at the bigger picture, with the aim for wider health improvements that can perk up thyroid functions. Moreover autoimmune causes of thyroid trouble are now common: approaches to these can be seen in articles in Part 4 of the Immunity Issue of this Gazette.

For a deep dive please check out further resources:

Recent Comments