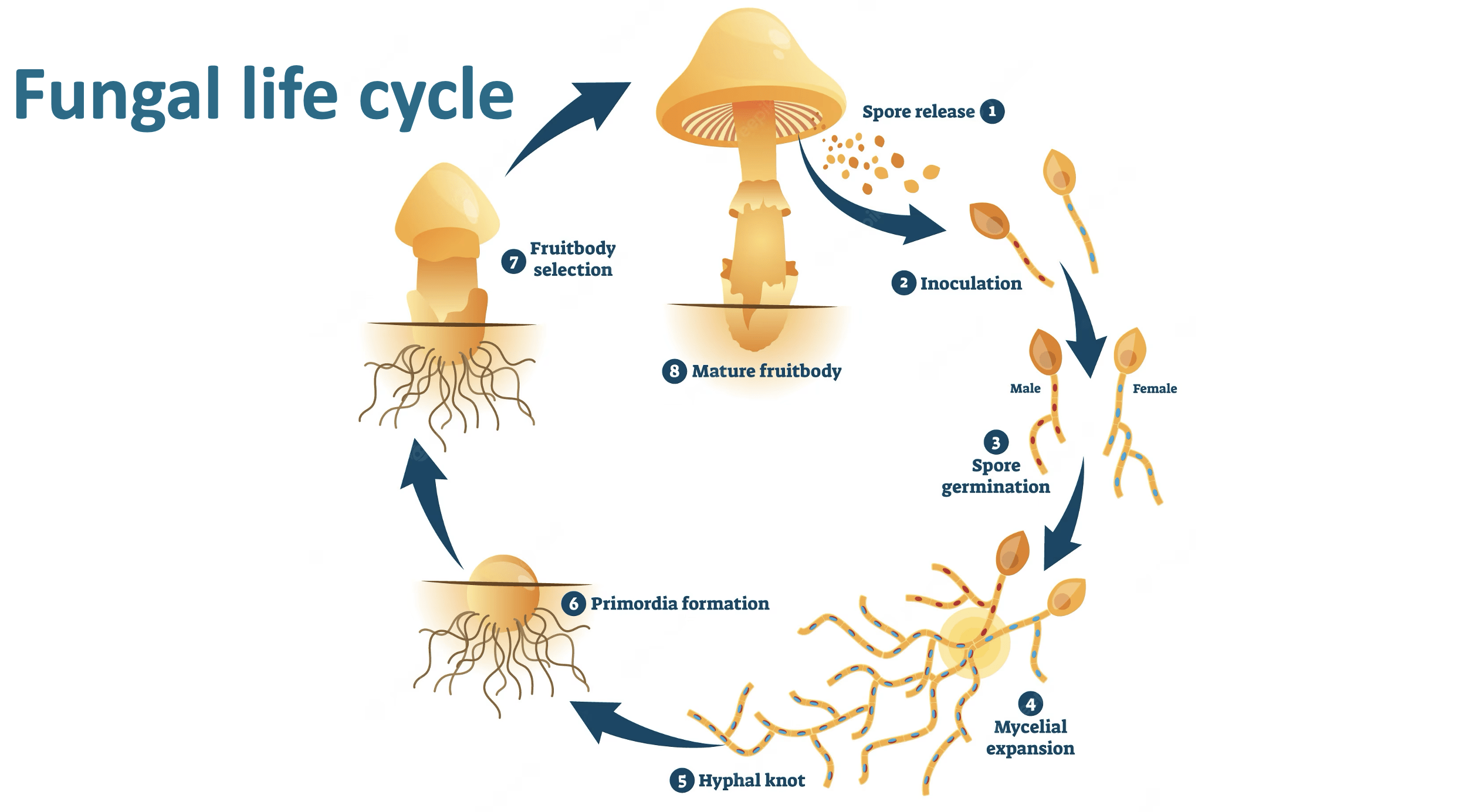

Fungi start as small filaments – hyphae. – formed into a network or mycelium. When ready to reproduce, the mycelium in many cases forms fruiting bodies that we recognise as mushrooms. These then produce spores, usually in massive quantities. In old or water-damaged buildings spore counts can be particularly high and are a major cause of allergies (see our article in Part 3). When spores germinate they produce hyphae and a new network begins.

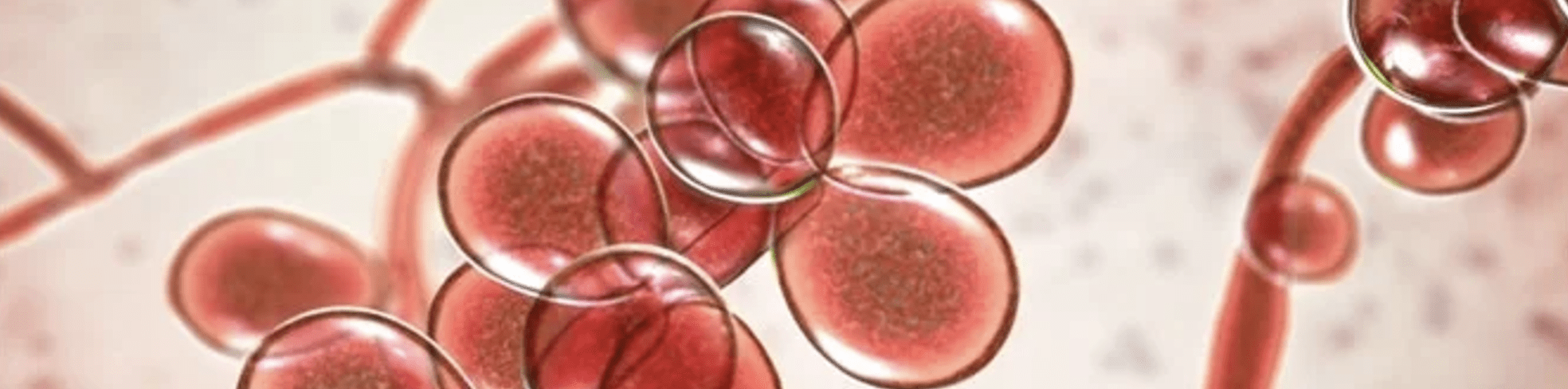

Some fungi – like Candida albicans – are ‘dimorphic’ and live both as mycelia and as single ‘yeast cells‘ which can remain as distinct living fungal entities in the own right (and not to be confused with baker’s or brewer’s ‘yeast’ which is a specific organism – see later). Under certain circumstances, for example when their population is threatened, these cells then produce hyphae again (see later).

The mycelial network infiltrates its surroundings searching for damp nutrient-rich material to feed on. Communication along the hyphae is amazingly sophisticated, including with electrical impulses, chemical signals and nutrients. So the mycelium as a whole shows intelligent searching behaviours, even navigating mazes in experimental situations! Unlike plants, which generate their food through photosynthesis, or animals which ingest their food, fungi have to immerse themselves in their food. They are thus entirely reliant on their environment: control this and you control fungi.

Fungi are also highly cooperative. They readily form ‘inter-kingdom’ alliances with other organisms to make the most of available opportunities. In the case of plants they provide nutrients and even communication networks, a phenomenon now known as the Wood Wide Web.

In lichens fungi partner with algae, to provide them with protection out of water in return for their photosynthetic nutrient generation. Almost all life depends on this partnership. For example, a key property of some lichens is being able to digest rock! For example lichens are the first to colonise new volcanic islands. By breaking rock down they generate nutrients, creating the soil from which plants can establish themselves.

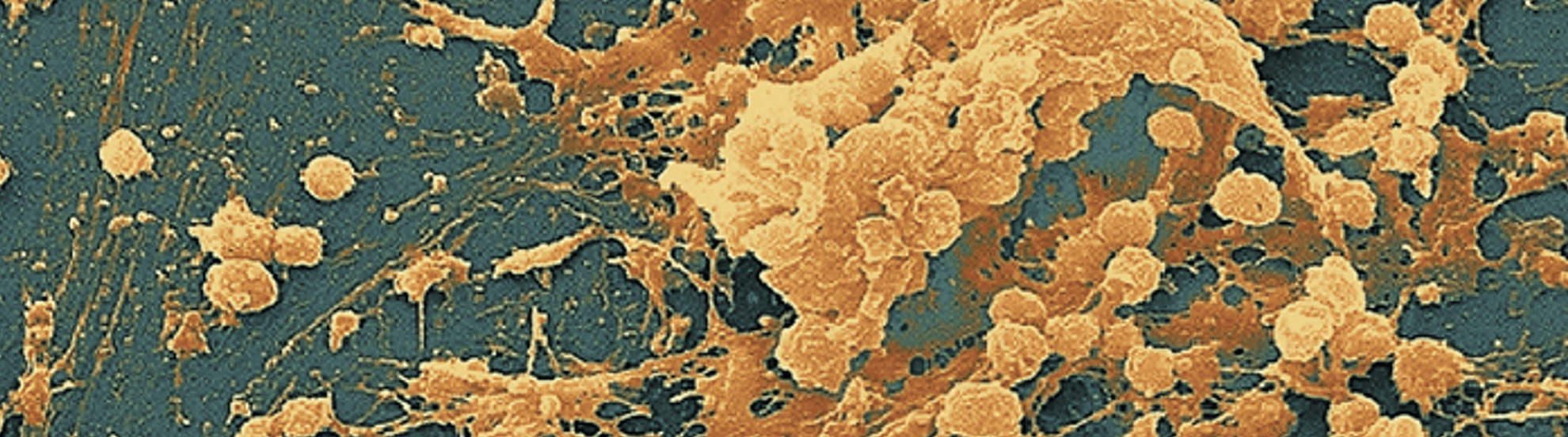

Less friendly are biofilms. These are also cooperative survival strategies, in this case with bacteria. Fungi can adhere to living and non-living surfaces, developing with their partners into highly organized communities and producing a tough polymer shell. Bacteria add their virulence in return for shelter and protection from environmental stresses, including antibiotics. Biofilms are thus a major cause of antibiotic resistance. Together the bacteria and fungi can also produce more inflammatory reactions from the body.

Biofilms under the microscope

However most of our engagement with fungi is positive. All our body surfaces have their own mostly healthy mycobiomes, especially in the gut. Indeed it seems that the gut mycobiome may precede – and even act as a trailblazer to – the microbiome, which then largely takes over.

The mycobiome also helps ‘train’ the innate immune system . Surprisingly this was first described for Candida albicans. Candida also primes aspects of adaptive immunity. Notably these benefits require it to stay in the gut. Candida’s protection extends against invasive pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus.

The other major fungal gut inhabitant is yeast (Saccharomyces spp). Together with Candida this has protective effects on the gut wall, protecting particularly against E.coli and C. difficile infection.

Yes, Candida (and yeast) are good for you – mostly!

Problems occur when there are immunological defects and ecosystem imbalance, and fungi are then able to proliferate into nutritious niches. The most prominent of these problems is candidiasis, in which there is Candida infestation outside the gut. This is associated with a wide range of problems: ‘mucocutaneous’ infections, such as oral or vaginal candidiasis (‘thrush’), and life-threatening systemic infections (a major cause of deaths in hospital).

There is a lot of confusion here. Candida invasion involves hyphal growth through the gut wall and beyond. Candida overgrowth in the gut involves Candida yeast cells – not hyphae. When yeast cells are numerous hyphae formation is not invoked. As we saw earlier this only happens when yeast cells are threatened. So Candida overgrowth does not lead to invasion and diets aiming to suppress overgrowth in the gut will not stop systemic candidiasis!

More seriously Candida is very efficient at forming biofilms, including in the mouth (eg plaque) and gut, with pathogenic bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori, Streptococcus, E.coli, Bacteroides, Clostridium, Klebsiella, Enterococcus and Actinomyces, and in the vagina with Lactobacillus. In cystic fibrotic lungs the partnership is with Pseudomonas. Candida biofilms are a major hospital hazard from inserted medical devices.

If Candida biofilms become a problem a good question is why? What provokes the Candida and partner bacteria to team up? Answer: biofilms are mutual survival strategies where opportunities or threats present. Provocations include alterations in the microbiome (e.g., due to antibiotics), changes in the host immunity (eg. another infection, immunosuppressant therapy, including steroids and chemotherapy, and stress), or breaches in gut wall integrity (eg surgical, alcohol excess, liver and other gut diseases). A major problem in hospitals is from biofilm-contaminated implanted medical devices. So most systemic candidiasis is a consequence of medical treatments.

Another significant health problem comes from mycotoxins, produced by some fungi (eg Aspergillus). These include aflatoxins, ergot, and ochratoxin which can cause cancer and serious liver and kidney diseases. They can grow on food items such as cereals, dried fruits, nuts and spices and thrive in damp and humid conditions. To avoid these at home

- inspect whole grains, dried fruit and nuts and discard any that look mouldy, discoloured, or shrivelled;

- make sure that such foods are stored properly, kept free of insects, dry, and not too warm; and

- do not keep them for long.

To manage fungal infestations the key is to reduce dampness. In the case of mould and spore exposure check our allergies post for things to be done with mouldy environments.

The most common internal fungal problems are associated with Candida albicans. As we have seen the majority of systemic candidiasis outbreaks, including oral and vaginal thrush, are associated with immune suppression and inserted medical devices. The focus here should be on building immune competence and recovering from illnesses or procedures (like repeated antibiotics or steroids) that may have knocked immunity (see the final post in Part 1). A leaky gut may also be involved and proactive attention to the health of the microbiome is always important.

As we have also seen Candida overgrowth in the gut is a separate issue from thrush and other manifestations of candidiasis. It is a popular diagnosis however and ‘candida diets’ are often recommended for thrush. More appropriately they are applied for symptoms like frequent bloating, IBS and associated energy deficiencies such as fatigue and brain fog. Such diets usually focus on reducing fermentable carbohydrates, sugars, and yeast products. This last is misplaced as we saw: baker’s or brewer’s yeast (Saccharomyces) is a different and competitive organism to Candida, but as most of these products are carbohydrates no harm is done and there may be other benefits.

The focus here really should also be on correcting the microbiome ‘dysbiosis’ that is overwhelmingly the problem. So antibiotic use is a major culprit, and the diet should include microbiome-friendly foods such as root vegetables, pulses, non-gluten whole grains, fermented foods and other probiotics. Highly processed foods have been shown to be disruptive in their own right so should always be reduced.

There is an interesting traditional insight. We saw that dampness is a constant in fungal overgrowth. Historically, this has long been associated with disease too. In India and other Asian traditions words for damp and disease are the same, and in western history disease was often seen to lurk in low-lying areas near water (eg in former dockland districts). Terms like ‘contagion’ and ‘miasma’ (bad air) were synonyms for infectiousness before Louis Pasteur’s Germ Theory identified microbes as causes. All this may now seem primitive and misleading but there is a useful case to be made by pursuing the imagery further.

Many problems with chronic infections and especially with fungal infections also coincide with symptoms that would have been described in older systems of medicine as ‘damp’ . ‘Cold damp’ was associated with fluid congestion, sluggish metabolism, copious mucus and joint pains and linked to low metabolic energy (or ‘cold’). ‘Damp heat’ (or equivalent terms) was associated with intolerance to humidity, persistent gut infections, greasy skin and especially liver problems. Both of these symptom patterns are often associated with people suffering fungal overgrowth. In all traditions of medicine damp was seen first to affect the functions of digestion. Two of the most powerful digestive remedy groups were thus also classified as ‘drying’: the heating and drying spices, and the cooling and drying bitters. Given both of their possible roles in improving the microbiome and gut wall integrity, there are other reasons to include them in managing fungal problems and long personal experience in practice confirms that this is often very helpful. Research findings also support the Candida management benefits of turmeric, cinnamon, garlic, cloves and barberry from these groups.

For a deep dive into the wonderful world of fungi check out this book

Sheldrake, M. (2021). Entangled life: How fungi make our worlds, change our minds and shape our futures. Vintage.

and these review papers:

Johnston E, & Brewer G. (2023). Mycelium: Exploring the hidden dimension of fungi | Kew.

Recent Comments