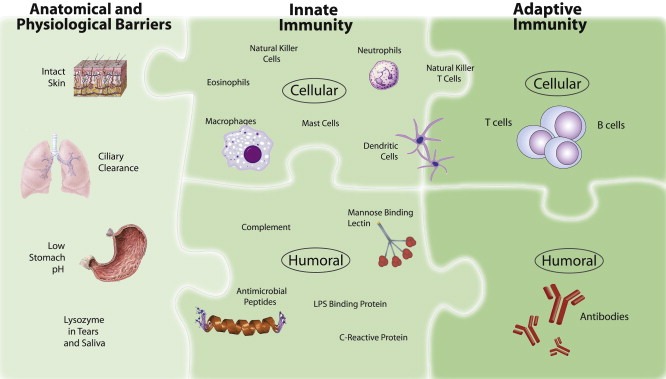

Our innate immune cells and digestion are backed by a very sophisticated defence infrastructure called the adaptive immune system. This is more complex and also more likely to go wrong.

The adaptive (acquired or specific) immune system is a sophisticated development of the immune system, found only in vertebrates. One proposal (in the third paper listed below) is that it is a management response to the much more highly developed gut microbiomes in vertebrates.

It is formed of a type of white blood cells called lymphocytes. These include B cells (or ‘plasma cells’) and T cells. They are responsible for mounting tailored responses to foreign molecules, in the context called ‘antigens‘.

Unlike the immediately active innate immune system, the adaptive response to a new antigen encounter can take days. However on the basis of this encounter, B- and T cells produce ‘memory cells’ which can respond quickly to repeat exposures. Memory cells are the aim of vaccination.

B cells have two major functions: they produce antibodies (technically immunoglobulins) to neutralize antigens and they also present these antigens to T cells. In an infection antibodies can coat germ walls and initiate one of three measures. 1) Neutralization prevents the pathogen from binding and infecting host cells. 2) In opsonization, an antibody-bound pathogen serves as a red flag to alert immune cells like neutrophils and macrophages, to engulf and digest the pathogen. 3) Complement is a cascade of enzymes that act like limpet mines to directly destroy bacteria and other danger cells (cobra venom uses the same processes!). This emphasises how seriously this wing of the immune system takes its work: it effectively risks damaging its hosts in its priority to clean the circulation. It also reminds us that the adaptive immunity is intrinsically more dangerous than the innate immune system. It is a theme we will return to in our final article in this introduction.

The most common type of antibody produced by B cells are immunoglobulin G (IgG); other important types are associated with the gut wall: IgA, IgD and IgM. There are also IgE antibodies most associated with basophils (‘mast cells’): these are designed to target large parasites like amoebae and worms, but are mostly associated in modern times with allergic responses.

T cells have roles that include killing infected cells and activating or recruiting other immune cells. CD8+ T cells recognize and remove virus-infected cells and cancer cells. The CD4+ T-cells (‘T helper cells’) are responsible for coordinating immune resposes to bacteria and other pathogens. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) monitor and inhibit the activity of other T cells. They prevent adverse immune activation and maintain ‘tolerance’, the prevention of immune responses against the body’s own cells and antigens.

As well as targeting antigens and damaged cells lymphocytes of the adaptive immune system can release powerful proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-12, tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). These play crucial roles in initiating and sustaining inflammatory responses.

However, as a powerful reminder of the dangers of a disturbed adaptive immune system, these cytokines can also damage the surrounding tissues (eg the bone loss in periodontal gum disease). In extreme conditions (eg as was seen in the most severe Covid infections) the adaptive immune system can create cytokine storms, excessive and uncontrolled release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that can lead to severe tissue damage. This was a time when talking about ‘boosting immunity’ became almost dangerous!

To balance such risks, the adaptive immune system also produces regulatory cytokines like IL-10 and IL-4, which can prevent excessive inflammation by suppressing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. However we are beginning to see reasons for another view, that we will explore in the next post, that we could do better to reduce provoking the adaptive immune system wherever we can.

To read further on adaptive immunity and its place in our immune system try:

Kaufmann SHE. (2019) Immunology’s Coming of Age. Front Immunol. 10: 684

McFall-Ngai MJ. (2007) Adaptive immunity: care for the community. Nature 445:153–153

Recent Comments